Ready for Takeoff: The Story of Longines and the Pioneers of Aviation

Share

Daring pilots relied on Longines watches aboard their flying machines in the 1920s and 1930s. The brand’s recently launched Spirit models recall this exciting history.

Freezing cold. Deafening noise. Leaden fatigue. He’s been flying for 11 hours and now night has fallen over the Atlantic Ocean. It will be more than twice as long before he lands. Charles Lindbergh is alone. He had already been awake for 23 hours when he took off from Roosevelt Field on Long Island. Now he’s struggling to keep his eyes open. The cold is his ally: the cockpit is open and a frigid wind whistles around his ears and ceaselessly shakes his plane. Despite thick gloves, his hands are nearly numb. But he knows he will persevere. Not just to claim the $25,000 prize that American hotelier Raymond Orteig has offered to the first person that can fly nonstop from New York to Paris, but to become immortal. When Lindbergh finally lands in Paris at 10:22 p.m. local time, tens of thousands of enthusiastic spectators cheer him and crowd around his plane, the Spirit of St. Louis.

The American pilot traveled 33 hours and 39 minutes from takeoff to landing. Lindbergh’s flight time was officially measured by a watch manufacturer from Saint-Imier in Switzerland’s Jura region on behalf of the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI). That manufacturer was Longines, a brand already well known among aviators. This was mainly due to John P. V. Heinmuller, head of the Wittnauer Company in New York, which distributed Longines watches in the United States. Heinmuller was an avid pilot himself who knew many aviators personally. He recorded and certified numerous record-setting flights in the 1920s. The Longines head office, which he visited several times, received valuable information from him about the special capabilities that pilots of that era needed from their on-board chronometers and wristwatches.

Longines and Record-setting Flyers

One of the first pilots to take Longines’ watches with them during their record-setting flights and on attempts to set new records was Swiss pilot and photographer Walter Mittelholzer. He relied on a Longines on-board chronometer in the winter of 1924-’25 during a four-week trip in several stages, from Zurich to Tehran. Mittelholzer again relied on Longines’ timepieces on an even more famous journey from Zurich to Cape Town that stretched from December 1926 to February 1927. But Longines’ reputation had long since extended far beyond Switzerland. After all, the company had served as official timekeeper for the FAI since 1919 and timed no fewer than 34 record-setting flights by the beginning of World War II. Longines built its first on-board chronometer for the cockpit in an aluminum case in 1915. Longines wristwatches, such as the chronographs with Caliber 13.33Z, first produced in 1913, were also popular among pilots. This single-button chronograph movement with a ratchet wheel and manual winding was appreciated mainly for its high precision; it could time elapsed intervals to a fifth of a second up to half an hour in duration.

Immediately after Mittelholzer, other aviation pioneers took Longines chronometers with them when they sped down runways with their sights set on breaking records. The Italian military pilot Antonio Locatelli flew from Ghedi, Italy, to Iceland in 1925. And shortly afterward, his compatriot Francesco de Pinedo traveled for several months in a seaplane on a journey that would take him to four continents. In June 1927, shortly after Lindbergh’s transatlantic flight, American pilot Clarence Duncan Chamber was the first person to carry a passenger aboard a nonstop flight from New York to Eisleben, Germany. Longines also kept time in 1928 aboard the “Southern Cross,” a three-engine Fokker F.VIIb-3m piloted by the Australian aviator Charles Kingsford Smith, whose feat made him the first pilot to fly across the Pacific Ocean from the United States to Australia.

Women Aviation Pioneers

Not only men, but also many women, ascended into the adventure of flight. One of the best known was Amelia Earhart. She had already worn a Longines watch in 1928 when she became the first woman to cross the Atlantic in an airplane, albeit as a passenger. She set a far more significant record four years after as the first woman to fly solo and nonstop across the Atlantic, from Canada to Northern Ireland in just under 15 hours. She wore the same Longines watch that had kept time for her in 1928.

Elinor Smith was another woman who made aviation history. After piloting an airplane alone at the age of 15, this American aviator became the world’s youngest licensed pilot one year later. She went on to set several additional records. For example, when she was 17, she spent 13 hours and 16 minutes alone in the cockpit, thus setting a new world record for women. In 1930, she flew higher than any woman — or any man — had ever flown, piloting her aircraft to an altitude of 27,418 feet. For this flight, too, she relied on timepieces bearing the Longines logo. After landing, she wrote a letter of thanks to Longines in Saint-Imier, saying that the watches functioned perfectly at all times.

But the list of record-setting female aviators is far from over. American aviator Ruth Nichols became famous in 1931 when she set a record, which she still holds to this day, as the only woman who simultaneously set the world record for altitude (28,743 feet), speed (211 mph) and long-distance flight (1,977 miles). From that year on, Nichols relied on Longines watches for all of her important flights. So did British pilot Amy Johnson who, with a “Weems” on her wrist, flew from England to Cape Town in 1932 in just four days, six hours and 54 minutes, thus breaking the record held by her husband Jim Mollison for this same route by 10 and a half hours.

The American polar explorer Richard E. Byrd also contributed to Longines’ steadily growing fame. Byrd had already made a name for himself in 1926, when he and his chief pilot Floyd Bennett attempted to become the first aviators to fly over the North Pole. Byrd didn’t quite accomplish this feat, but he achieved a similar one over the South Pole in late 1929. On the Antarctic expedition, Byrd, a perfectionist, carried a number of certified marine chronometers and wrist chronometers with him. Afterward, he sent a telegram to Saint-Imier saying that the Longines instruments and chronometer wristwatches that the Wittnauer Company in New York had provided for them had proved to be extremely satisfactory.

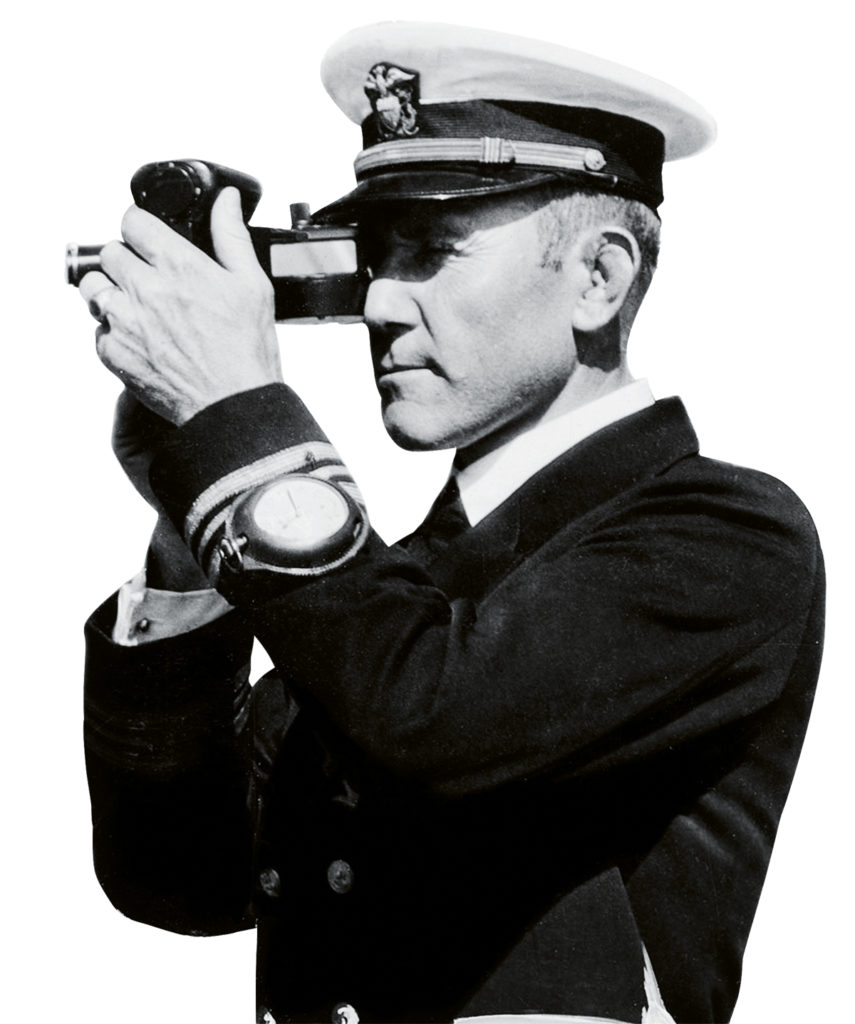

The Weems Second-setting Watch

Among the watches referred to by Byrd was the Longines watch known to collectors as the “Weems,” named after U.S. Navy officer Philip Van Horn Weems. He designed a wristwatch especially for aviators that allowed a pilot to synchronize his watch’s second hand with a radio time signal with unprecedented speed. Prior to Weems’ invention, a pilot had to pull the crown out and adjust the watch’s hands while wearing flight gloves, frequently resulting in the pilot losing the exact second and often the minute as well. Weems calculated that, depending on the aircraft’s speed, a deviation of as little as 4 seconds could send an aircraft off course by a mile or more — with potentially fatal consequences. So he designed a rotatable, centrally positioned subdial with markings for 60 seconds. When a pilot heard the time signal — and without jeopardizing his watch’s precise timekeeping — they could quickly align the zero on the seconds disk with the moving second hand.

Longines started producing the Weems Second-Setting Watch in 1929. Due to Byrd’s successful expedition to the South Pole and his praise for this watch, the entire international aviation scene was soon talking about the manufacture in Saint-Imier.

It’s interesting to note that Charles Lindbergh did not have a Longines watch on board during his famous Atlantic crossing in 1927. He never said a word about his wristwatch, and its manufacturer remains unknown to this day. Thanks to the instruments in the cockpit, he was able to navigate successfully to his destination, but his safe arrival in Paris was almost a miracle. First, to minimize weight, Lindbergh had dispensed with important navigational aids. Second, his pilot’s seat was directly behind the engine, so he could not look forward directly, but only through a periscope. Moreover, he was anything but an experienced navigator. Today, historians of aviation agree that in addition to his optimism and perseverance, Lindbergh was also extremely lucky. Other pilots were not as fortunate. In 1927 alone, no fewer than 15 pilots died in attempts to replicate Lindbergh’s transatlantic flight. In most instances, insufficient knowledge of navigation was the primary reason for their demise.

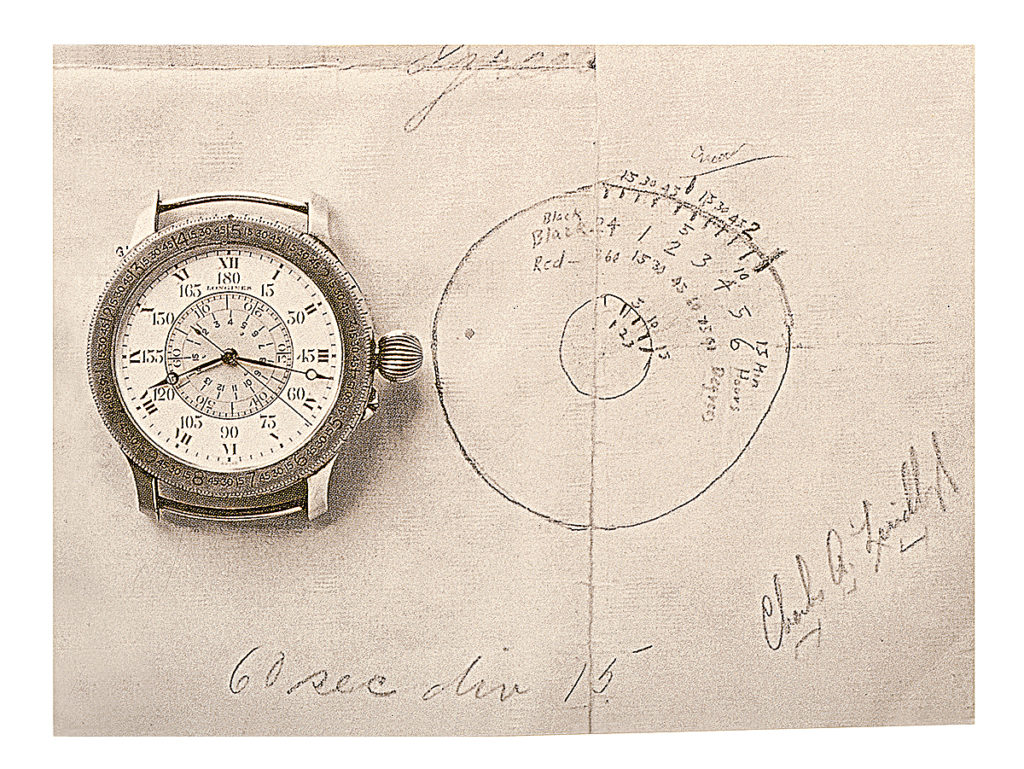

Lindbergh’s Hour-Angle Watch

When Lindbergh himself lost track of his position on a flight near Cuba in 1928, he turned to Weems for a month’s training in astronomical navigation. After learning about Weems’ ideas for the Seconds-Setting Watch, Byrd began sketches for a watch that would enable a pilot to navigate by determining longitude. Lindbergh’s design included a dial on which the hour hand not only indicated the 12 hours, but also showed the corresponding degrees. For example, 12 is equivalent to 180 degrees. The minute hand pointed to the arc minutes, which were printed on the rotating bezel (15, corresponding to 60 minutes). And in the center of the dial was a subdial that could be adjusted in the same way as its counterpart on the “Weems.” On Lindbergh’s watch, this subdial could be used in tandem with the second hand to read another 15 arc minutes. The values shown by the three hands could then be added together and the difference between true and mean solar time could be calculated by turning the bezel. Like Weems before him, Lindbergh contacted Longines, which agreed to collaborate with him. In 1931, the Swiss began producing the Lindbergh Hour Angle Watch, both as a 47-mm-diameter wristwatch with Caliber 18.69N and as an on-board chronometer with the same movement but encased in a wooden box. Many aviators ordered and used the Hour Angle Watch as a navigational instrument on their airborne adventures in the 1930s.

Howard Hughes and the Siderograph

Longines went one step further in 1938 with the development of the Siderograph. This watch, named after sidereal time (temps sidéral), completely dispensed with the representation of civil time (mean solar time) and showed only side-real time, which it displayed via various scales marked on the dial and on the peripheral bezel in hour angles, minutes and arc minutes. The advantage for a pilot was that the conversion from solar time to sidereal time was omitted, so the aviator could calculate the aircraft’s position faster. (In addition, this watch made pilots and navigators independent of the sun, so they could also navigate at night.) Caliber 21.29, which had been developed in 1910 and was considered to be an especially accurate movement, ticked inside the Siderograph’s lightweight and antimagnetic aluminum case.

The famous entrepreneur, Hollywood producer and film director Howard Hughes was one of the first aviators to use the Longines Siderograph. Hughes had also earned a name for himself as a pilot by setting several records aboard airplanes that he had developed himself. In 1935, for example, he set a new speed record of 352 miles per hour and flew from Los Angeles to New York in the record time of seven hours, 28 minutes and 25 seconds. In 1938, it took him and his Lockheed 14N2 Super Electra only three days, 19 hours and 14 minutes to circle the Northern Hemisphere. Hughes’ Siderograph accompanied him on that record-setting 14,800-mile trip via Paris, Moscow, Omsk, Yakutsk, Anchorage, Minneapolis and New York. While Hughes was refueling in Paris, Longines’ French branch sent a tele- gram to Saint-Imier, notifying headquarters that Howard Hughes’ aircraft was equipped exclusively with Longines on-board chronometers and chronographs.

With the rapid technological development that aviation underwent during and after World War II, mechanical timepieces, including those made by Longines, quickly faded into the background. But after the Quartz Decade of the 1970s, the renaissance of the mechanical watch set in, and the developers in Saint-Imier once again recalled the classic pilots’ watches. To celebrate the 60th anniversary of Lindbergh’s landing in Paris, Longines launched an anniversary collection of the Hour Angle Watch, which was followed by other models in subsequent years. Most of these were variations of Lindbergh’s watch, but there were also Weems models and limited editions based on historical Longines pilots’ watches, such as the Avigation Type A-7 with its dial turned 45 degrees to the right and the Twenty-Four Hours with its 24-hour display.

The Spirit of 2020

The new Spirit collection, which Longines launched in early summer 2020, recalls the brand’s aeronautical roots. Classic Longines pilots’ watches inspired many details in this collection’s design. This is particularly true of the watch’s excellent legibility thanks to the clearly arranged dial, Arabic numerals and ample luminous material on the hands and numerals. It also applies to the large crown, although this one isn’t quite as huge as its historical counterparts and it’s also not in the shape of an onion. The diamond-shaped hour markers trace their ancestry to various Longines pilots’ watches from the 1930s. Longines chose not to include a special mark for the 12: some of the classic watches have such a mark, for example, in the form of a red line or a triangle, but it is absent on many models. The Lindbergh Hour Angle Watches, for example, do without it.

Up until recently, the Spirit models all came exclusively with a date window at 3 o’clock. While even the models with a moderate diameter of 40 mm appear to be a bit too large for the automatic Caliber L888.4 (ETA A31.LII) used inside, Longines is now also offering a no date version in titanium for those looking for a more balanced dial.

What definitely makes the Spirit models special are the five stars on the dial. These also come from the company’s history: the stars were used to indicate the fine quality of the movement in models like the Admiral that was popular in the 1960s and 1970s. Five stars were the maximum and represented the highest quality level. This still holds true today. The aforementioned Caliber L888.4 has a silicon hairspring and is certified as a chronometer by the official Swiss chronometer-testing authority COSC. The same certification applies to Caliber L688.4 (ETA A08.L01), which ticks in the chronograph, with ratchet wheel and automatic mechanism. Both movements amass a longer power reserve than standard ETA calibers: 66 hours for the chronograph and 72 hours for the three-hand watch.

We were pleased to discover that these five stars are now individually applied, which requires more effort than in the classic models where the stars were connected in the center by a bar, so that only a single component needed to be inserted during the assembly process. The new version certainly looks nicer.

Variations and Pricing

Anyone considering the purchase of a Spirit can choose from several versions. Both the three-hand watch and the chronograph are available with three different dials: matte black, blue with a sunburst finish or silver with a grained surface. Each version is available with either a steel bracelet or a leather strap, and the choice of wristband does not affect the price. Furthermore, Longines gives a 5-year warranty on all Spirit models. The 40-mm automatic model costs $2,150, the 42-mm automatic watch sells for $2,250 and the chronograph, also 42-mm in diameter, is priced at $3,100.

There is also a Prestige version of the three-hand watches. Those who opt for this timepiece receive three different wristbands: a steel bracelet, a dark brown leather strap and a brown NATO-style leather strap. Choosing this option costs $2,650 for the 40-mm version and $2,750 for the 42-mm model.